Townland boundaries Durrus Civil Parish, photograph Danno Mahony in Irish Army 1933, photo Richard Townsend Ireland’s oldest magistrate

08 Saturday Oct 2011

Posted in Uncategorized

08 Saturday Oct 2011

Posted in Uncategorized

07 Friday Oct 2011

Posted in Uncategorized

REPORT from Dr. Stephens to the Board of Health on the Bantry

Workhouse

Bantry, 20 February, 1847

Sir,

I have the honour to state for the information of the Central Board of Health, that pursuant to their orders I visited the Bantry Workhouse yesterday, and made enquiry into the character of the sickness prevalent in it, also as to the ages of the patients who died in the week ended the 6th instant, the duration of their stay in the workhouse previous to death, the state of the house as to ventilation and the diet and drink for the sick, together with the number of cubic feet allowed to each inmate in the sick and healthy wards.

With reference to the workhouse, I find it clean and orderly; the wards are spacious, and not having the number of beds they are capable of accommodating without inconvenience, the air of the house generally good, with the exception of the male infirm ward, in which the air was most impure from want of ventilation, as also the male dormitories for boys from six to ten years of age, whose habits are filthy; the same to be said of the female day-room, which is also a nursery for children

and their mothers; the air of this room was most impure, the women being very inattentive to the habits of decency, which the matron, who is herself most orderly, finds it very difficult to make them observe. ‘

The enclosed paper contains the ages of patients, their stay in the house, and the number of cubic feet allowed to each lunatic.

Language would fail to give an adequate idea of the state of the Fever Hospital; such an appalling, awful, and heart-sickening condition as it presented I never witnessed, or could think possible to exist in a civilized or Christian community. As I entered the house, the stench that proceeded from it, and prevailed through it, was most dreadful and noisome; but oh, what scenes presented themselves to patients lying on straw, naked, and in their excrements, as light covering thrown over them; in two beds, living beings beside the dead, in the same bed with them, and dead since the night before. I saw a woman who had been delivered but four days, almost expiring, with her wretched infant nearly suffocated; I administered at once wine, and had warmth applied, as there had been no medical attendant appointed during the illness of Dr. Tisdall, one of the medical men of the town, I was told had been there two days before; no medicine, no drink, in dirt, no fire, the unhappy beings who were able to express their wants crying out for drink, water, water, asked for, but no one to give it to them; others crying out for something to eat, as they said they were starved; many imploring to be taken out of it as they were not sick, but weak; thirty soon were found fit to be removed. The prevailing disease is dysentery, rendered highly contagious from the fetid state of the several wards.

The wards are saturated with wet and ordure, the walls -marked with the same. No nurses in the house except one of the paupers, totally unfit for the duties, every person being afraid to enter what was considered a pest-house; it is useless to enlarge or dwell further upon this revolting subject.I directed the clerk

of the union to bring to the board room any guardian or guardians he could find; three came, and in the presence of the chaplains of the house, and the master and matron, I laid before them the state of things I had just witnessed, with feelings I will not attempt to describe, and stated to them what should be done to arrest the frightful evil so widely spreading. In the yard, filthy beds and bedding were heaped up and allowed to remain there; the same state of things in the infirmary, where dysentery was almost universal.

The supply of water for the workhouse being carried by women: the want of it at present was great, from the great increase of washing. It is said to be not good; it is impregnated with iron, and much disliked

Having done all that was possible for me to do here I purpose to proceed to Cork, to attend the meeting of the Board of Guardians there on Monday, after which I shall proceed to Mitchelstown, where I hope to be on Tuesday to comply with the wishes of the Central Board of Health. –

I have, &c.

(Signed) R. Stephens

A sworn enquiry was held and the physician was called on to resign.

07 Friday Oct 2011

Posted in Uncategorized

Godwin Swift letters Crookhaven 1757

Extract from letter of Godwin Swift (Customs Man), 16th May 1757 from Crookhaven

‘Now with regard to the place and provisions: you are to know that you see nothing here but mountains of rock (not cliffs) and yet those rocks are more dear to poor people or strangers as the lands within 2 miles of Dublin. There is here undoubtedly great plenty of fish, yet the people are so lazy they’d rather live on salt mackerel and potatoes then give themselves the trouble to take fresh fish. There is no garden stuff here, very bad mutton and lamb, and no beef, not a tree or even a shrub within 8 miles of the place….

30th June 1757 ‘…nothing but rocky mountains around us for 20 miles, where not even a slide car can go the road, nor any other cattle than little horses bred and used to this country….you can’t conceive the wretchedness of it. We have neither bread to eat nor malt liquor wine or cider to drink, nor meat except a little mutton and bad lamb. Our liquor a bad toddy, our victuals potatoes and fish and lie in a cottage..

Toby Bernard, Mizen Journal 2004

Richard Griffith built the road to Skibbereen in the 1820s

Cork Customs Personnel:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1K9FbQLKPjRm9HLMNy99__AAMLmis519psiSvcP71Rts/edit#gid=0

07 Friday Oct 2011

Posted in Uncategorized

Carrigbuie, from George Bennett’s History of Bandon 1869

About five miles south-west of Bantry is the pretty little village of Carrigbuie. It is agreeably situated at the head of Dunmanus Bay–one of the great inlets from the Atlantic–and in a district where copper barytes, flags, and slate of superior quality, are to be found in abundance. The copper-mines in this locality are favorably known. The “south band,” which runs along the coast from Mizen-head to Roaring-water, has already produced copper-ore worth a hundred thousand pounds. The Bandon barytes mine has rewarded the energy and perserance of a Liverpool company with a yield of several thousands of tons. Flag quarries, which overhang the sea, produce flags of a fine buff co lour, and are represented as capable of being worked to great advantage; and the slate veins of Sea-lodge and Rossmore, already traced to a length of two miles, are found to have an average width of ninety feet. These are also worked by an English company, who has a ready market for their produce in France, as well as in many parts of England and Scotland. “After a careful and minute search of the Carrigbuie estate of the Earl of Bandon, we find,” say Messrs. Thomas and Son, the eminent mining engineers, who have been for a long time acquainted with that country, “that there are no less than thirteen ploughlands that contain minerals, offering every inducement to the capitalist to develop them.”*

Carrigbuie-that is, the yellow rock-lies in a well-sheltered vale, through which flows a noisy stream, which empties itself into the bay here. Previous to the expiration of the lease by which Carrigbuie was held under the Earls of Bandon, it consisted of but a few thatched cabins, which are described as being both filthy and miserable. These have now disappeared; and a great improvement has taken place in its appearance, as well as in its prospects, since it has come into Lord Bandon’s hands. The mud cabins have been replaced by rows of clean and substantial houses. Good-sized shops display tempting wares in their windows and on their shelves. A post-office delivers and dispatches the inhabitants’ letters. A dispensary is furnished with every requirement for the sick; and a hospitable hotel, with its well-supplied table and its comfortable accommodation, helps to persuade the traveller that he is at home.

Durrus Church is but a short distance from Carrigbui It was built about the year 1798, on the site of a chapel-of ease, which was used for divine service before the breaking out of the great rebellion in 1641. After the suppression of that memorable rising it does not appear to have been used again; as in little more than sixty years afterwards, although its walls (which were built of large square stones, imbedded in clay mortar) were standing, its roof was gone.

Most of the lands of Durrus and Kilchohane were forfeited by the Irish proprietors in 1641. In the reigns of William the Third and Queen Anne, the principal landed proprietors in this immense district were Judge Bernard, Lord Angelese, Colonel Freke, Lord Cork, Mr. Hull, Mr. Hutchins, and Major Eyre.

*Vide Descriptive reports on the mines, minerals, flag, and slate quarries on the estate of the Earl of Bandon in the south-west of the county of Cork, printed at the Mining Journal office, Fleet Street, London, 1865.

07 Friday Oct 2011

Posted in Personal Memoirs, tim healy ballarat australia

Tags

australia, ballarat, bantry, durrus, Food, Healy, history memoir, ireland, Irish Free State, james, Methodism, Moloch, skibbereen, tim healy

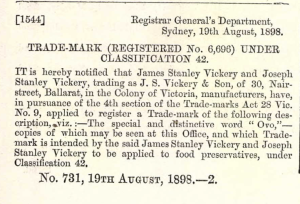

Recollections of James Stanley Vickery as a grandchild in Molloch, Durrus, Bantry (1829-1911), House c 1740-70 and Probably Prior House in ruins Pre-1740

Mulloch:

In Australia:

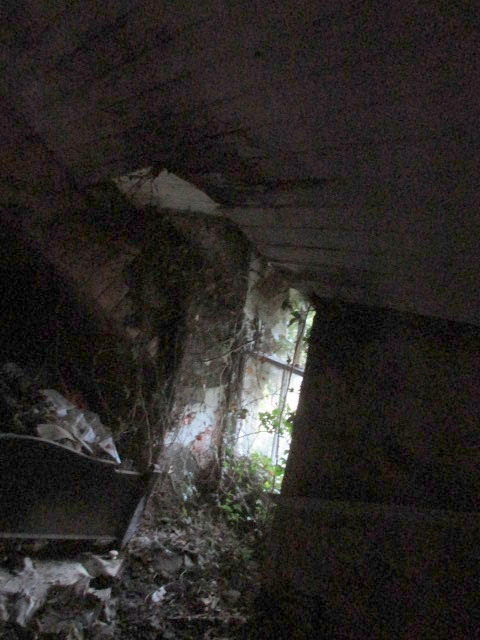

Enclose are picture of the house, yard and well in January 2016. Also enclosed in the probably earlier Vickery house possibly before 1740s situated just a distance from the present house which was lived in up to the 1980s by the Swanton family who are probably related by marriage to the Vickeries.

The farm comprised 170 acres large farm for the area.

In the Bantry Estate Records the Vickeries and their kinsmen the Warners and O’Sullivans were noted as yeomen farmers. Like the Warners, the Vickeries probably originated in nearby Rooska and are most likely in the Bantry area pre 1700. The Warners apart from farming also held various farms which were sub let as did the Tedagh Sullivans, The Warners had a reputation for hard work, honesty and fair dealing which transferred to their Cork descendants, the Musgrave family (Supervalu) on the female line. Like the Vickeries they were Church of Ireland and late converted to Methodism.

House 1740-70, and probable pre 1740 house:

There is a debate as to whether he has all the family information correct. Entire Recollections:

https://plus.google.com/photos/100968344231272482288/albums/5884047429692369217?banner=pwa

In Frank Callanan’s biography of Tim Healy (Politician, barrister, Governor General of Irish Free State) he states that his grandfather Healy was a classical teacher in Bantry. In the recollections James relates how he was taught by a master called Healy it may be the same man.

The above house may have been the residence of James Stanley Vickery. It is owned by Mr Jimmy Swanton, Moloch, Durrus and was lived in until around 25 years ago.

These are an extract of the early memories of James Stanley Vickery who later went to Australia. He founded a business in Ballarat dealing in chemicals, food products etc. This successful business remained in the Vickery family until World War 2.

James Swanton was a notable local figure and was a Cess payer representative in 1834:

1834. NAMES and PLACES of RESIDENCE of the CESS PAYERS nominated by the County Grand Jury at the last Assizes, to be associated with the Magistrates at Special Road Sessions to be holden in and for the several Baronies within the County, preparatory to the next Assizes, pursuant to Act 3 and 4 Wm. 4, ch. 78.

| Barony of Bantry | William O’Sullivan Carriganass, Kealkil | Michael Sullivan, Droumlickeerue | John O’Connell, Bantry | Richard Levis, Rooska |

| William Pearson, Droumclough, Bantry | Daniel O’Sullivan, Reedonegan | Jeremiah O’Sullivan, Droumadureen | John Cotter, Lisheens, | James Vickery, Mullagh, Bantry |

| Rev. Henry Sadler, The Glebe | John Godson, Bantry | Richard Pattison, Cappanabowl, Bantry | John Kingston, Bantry | Samuel Vickery, Franchagh |

| William Pearson, Cahirdaniel, Bantry | Robert Vickery, Dunbittern, Bantry | Daniel Mellifont, Donemark | John Hamilton White, Droumbroe | Samuel Daly, Droumkeal |

He was born in Skibbereen and after his parent died of Asiatic cholera in 1832 he and his two sisters went to live with their grandparents at Moloch, Durrus 1832-36. His grandfather James had formerly farmed in Rooska and held the farms by lease from Lord Bantry at a modest rent and the family was comfortably off. There was a suggestion that the family were involved in smuggling and the Vickerys are reputed to descend from two brother shipwrecked in Bantry c 1740. In later years his grandfather became religious and a leading light in the Methodist movement. James spent 4 years in Moloch and gives an interesting account of life at the time. In his grandfather’s time there were good prices for produce but hard to get to market. There were no proper roads and his grandmother or aunt had to go to Bantry it was on horseback in the old fashion pillion. When wheeled vehicles arrived on the farm but were used with a feather bed.

The house was a two storey one with slated roof. There was rough comfort with turf fires. Wood was dug out of the bog sufficient to make rafters for the outhouses, oak as black as jet. There was a resinous wood found in great plenty out of which when dry they made good torches which was often used instead of a candle. In 2008 there are still quantities of bog oak in the nearby Clonee bog.

Bacon hanging from the kitchen rafters, potatoes in their prime, with oatmeal porridge, wholemeal bread, milk and butter and honey in abundance. It was the finest honey country around with the hill tops covered in native heath and the fields in red clover. There was the best kind of fish with very little of either beef or mutton or even the staple commodity bacon. Off the wild coast grew some edible seaweeds which made a cheap pleasant and extremely wholesome food. Carrageen moss had long formed a medical food of great value. Shellfish of various kinds were cheap, crab of large size were very common. Oysters very large and plentiful were not much in use. Everything was both cheap and plentiful with the exception of that most needful of all money to purchase. He knew of turbot sold at 2/6 which would cost 20/- in Billingsgate. The people though living close to the sea were not strictly seagoing unlike the Cornish folk on the opposite coast of England.

Spinning wheels would be making music the large one for wool and the small one for flax. The articles made from these materials were very coarse but strong and endurable. Farming implements were of the primitive kind, a one furrow plough scythe, sickle and flail. The latter consisted of two well seasoned ashen sticks about five feet long united together with strip of green hide. With this the corn was threshed and it was a pleasant sight to watch the active young men face each other at the work. There was not even a winnower in use and the corn had to be separated from the chaff by holding it up to the wind the corn falling on a sheet of tarpaulin spread on the ground to receive it. Foreign matter small stones and clay was later removed prior to going to the mill by spreading it on a large kitchen table and the women of the house picked it out.

After killing the fatted cow the rough fat was melted and used in the making of candles usually by the slow process of dipping. A good washing potash lye was made from ashes of burnt furze. Starch was made from the farina of potatoes. A kind of tea was made from a certain kind of mint, china tea being a luxury forming often times a valued present from well to do friends. A sweet and mild alcoholic drink was brewed from honey called metheglin (spiced mead). Sickness was treated with simple herbs grown in the garden. He well remembered the abhorrent taste of tansy to kill worms and other parasites in the child’s interior. Whiskey was not forgotten no doubt having the well known peculiar flavour of genuine ‘Potheen’. It was very little used as a beverage by the family but as a remedy it had its place in emergencies. He dwelt on these particulars as they gave an insight on the common life of the time now passed away.

He recalls his grandfather’s death and the wake going over two nights with a professional keener.

He went around 1837 to a small private school in Bantry run by a man called Healy who was a Catholic. The new National schools had been boycotted by the Irish Protestants. Healy had attained a proficiency in mathematics but was extremely cruel, over one of the rafters he threw a small rope and tied it under James’s arms and hoisted him up swinging him gently and letting him feel the holly rod to the amusement of the other boys. His wife on seeing it stopped him and gave Healy a piece of his mind. Healy was later convicted of cruelty in front of the magistrates. James later went to live with relatives in Bandon and went to Australia in 1853. The house in Mulagh is the old Swanton farmhouse last occupied by Jimmy Swanton’s mother 1980s. and in fair structural condition. Sullivan

07 Friday Oct 2011

Posted in Irish words in use 1930s, Personal Memoirs

Tags

Agriculture and Forestry, business, Cattle, Horticulture, ireland gaelic hiberno-english, irish co clare, irish language relic durrus dun beacon, Meitheal, Poitín, Salach, Turfgrass, west cork bantry history

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1dLSWVUsYRVa2ViKqOHyj5sl6Plz-tzLLVgpQgU3gvQM/edit

Irish in ordinary speech 1930s

Adhastar, a halter

Ascail, armful, hay, straw

Aiteann Gaelach, Tufts of furze

Amadán, a fool

Ainniseoir, a miserable person

Asal, a donkey

Bacán, treadle of spade

Barrfhód, top sod (turf/peat)

Barrghaois, phosphorescence

Bainbhín, little banbh (piglet)

Bainne Buí, beasting (first milk of cow)

Bainnc cioch Anna, splurge,

Balcais, tattered clothes

Barra liobar, numbness in finger, parathesia

Bastún, blockhead, eejit

Beach Ghabhair, a wasp, horse fly

Beart, bundle on back

Birineach, short pointed rush

Blathach, buttermilk

Bladaire, a flatterer, blower

Bogan, egg without shell

Boithrin, laneway

Braon, drop (whiskey)

Bothán, hut, hovel

Bro, a quern

Brosna, firewood, kippins

Brus, small pieces (as of turf)

Buachalán, ragworth, noxious weed

Buarach, spancel (milking)

Budan, stump of animal’s horn

Buaileann Sciath, boaster

Buailtean, striking staff or flail

Cabóg, a rustic labourer

Cabhlach, ruin of an old house

Cadarail, gossip

Caibin, an old hat

Caillichin, ash plant (cattle herding)

Caoch, blind

Carraigin, edible seaweed, moss

Caoran, small piece of dried turf

Ceis, a young sow

Ceartaigh, as when milking

Codladh griffin, Pins & needles

cabhóg, old hat

Cip-idir-ril, commotion

Cisean, basket

Cleamhnas, made match

Cleas-na-peiste, a type of knot which kills worms in cattle

Cliotar, clatter

Cnaimhseail, grumbling

caipeis

Coincin, upturned nose

Cabaire Cailleach, an old hag

Caisearbhan, dandelion

Caol-fhod, narrow sod in furrow

Ceannrach, a halter or bridle

Ceartaigh, as when milking

Ceol, music

cip I’do ril, racket (disorder)

Ciaróg, beetle or cockroach

Ciotog, left handed person

Ciseach, path or bridge in wet ground, bog

Clais, furrow

Cliamhain isteach, Son-in-law in bride’s house

Corra mhiol, midge

Corra thronach, restless

Cleibhi, mantle over fireplace

Craobhabhar, Sty (eye)

Crobhnasc, Rope tied from cow’s foreleg to horn

Cruibin, Pig’s hoof

Cuingeal, Coupling rope ploughing

Culog, Riding behind another (horse)

Cupóg, dock plant

Cliotar, clatter

cnocan, hillock or knoll

Cniopaire, A miser

Codladh griffin, Pins & needles

Coinncin, Upturned nose

Cois ceim na trocaire, Three return steps when meeting a funeral

cri neatness

Corra-giob, posterior

Corrabhuais, smirk, concern, uneasiness

Corrathonach, restless

Crain, sow

Creathan, small potato

Creatar, drop of drink

cunsog, nest of honeybees

Croitin Cuas, narrow inlet of sea

Cuigion, chur

Cuirliun, curlew

Cunsog, nest of honey bees

Deoch an dorais, One for the road

Diabhal, devil

Doirnín, Handle of scythe

Dorn, fist

Dramhail, refuse, trash

Dreadaire, good for nothing

Driodar, dregs (liquid)

Duileasc, edible sea weed

Dreoilín, Wren

Duchas, heritage, likeness ancestor

Eascu luachra, a lizard

Eist do bheal, shut up

Faire go deo, what a pity

Failte, welcome

Fear a’ti man o’the house

Feasóg, beard

Feochadan, thistle

Fite fuaite, mixed up, entwined

Fionnan, coarse grass on hill

Flaithiúil, generous

Fluirse, plenty

Fothain, shelter

Fuachtan, chilblain

Fustaire, a fussy person

Follain, healthy

Fraochan, hurtleberrry

Fuadar, rush hurry

Gabhail, hay in two arms

Gabhairin reo, jack snipe

Galloge, gállóg’ would apply to the fork handle of a catapult as having its mouthful of sling shot.

Gaillseach, earwig

Gam, a foolish person

Garbhog, bees nest in a ditch

Garsún, a young boy

Gearrach, a nestling

Gealas, braces, suspenders

Gibiris, prattle

Giobal, rag

Gioballach, untidy

Glaise, stream

Glib, hair hanging over eye

Gligin, hairbrained

Gob, big mouth

Go leor, ample

Gollan, large standing stone

Gliogar, an addled egg

Grafán, grubber

Gramhar, loving

Grideal, griddle

Griosach, red coals in ashes in turf in morning

Grabhas, ceartaigh, milking

Hum no Ham, word or movement

Iomaire, ridge of potatoes

Ladhar, handful (oats for horse)

Lairin, a little mare or pony

Leadhb, a useless person

Leadranach, untidy

Leath Sceal, excuse

Liudraman, useless lazy person

Luban, loop, tangle

Hulla builin, outcry, noise of hunt

Laincis, spancel

Lamh laidir, violence

Leadranach, lingering, slow

Liobar, untidy, hanging lip

Lubaire, a rogue

Luidín, little finger

Meadhbhán, dilisk,edible seaweed

Mar dhea, as he says

Maith go leor, tipsy

Mointean, reclaimed bogland

Meiscre, cracked skin on hand

Meascan Mearai, bewilderment

Meitheal, a group of helpers

Mi-adh, misfortune

Mi na Meala, honeymoon

Murdail, horror of horrors

M’hanamsa, oh! My soul

Mothal, bushy hair

Munlach, animal urine, dirty puddle

Muing, a fen, morass

Oinseach, foolish woman

Ologon, wailing (bain si)

Pilibin Miog, lapwing, plover

Pleidhche, simpleton, fool

Poc-leim, jump with joy

Poitín, poteen, illict whiskey

Portach, bog

Praiseach bui, stirabout

Piseog, superstious practice

Plucamas, the mumps

Pocan gabhar, male goat

Portach, bog

Puca padhail, a toadstoll

Raidse, plenty

Ri Ra, bedlam

Rogaire, a lovable rogue

Ruthail, rooting (pig)

Ruaille Buaille, commotion

Siogan,

Sceabha, askew

Sciollán, cut potato seed

Scolb, thatching spar

Scoraiocht, nightly visiting

Sean Saor, Cheap Jack, dealer

Slisne, thin wedge, (under nail), tiny chip of wood

Spagai, clumsy legs

Raidhse, plenty

Ri-ra, fuss, commotion

Rogaire, rogue

Salach, Mud sludge at bottom of stream/river

Scailp, sod, a scraw

Sceabha, askew

Sceach, a thorn bush

Sceartan, tick, bug

Scolb, thatching spar

Scoraiocht, nightly visiting

Scrogall, throat

Si-gaoithe, whirlwind

Sibín, illict pub

Sleán, turf-cutting tool

Slachtmhar, tidy

Slibire, a tall ungainly man

Sláinte, health

Slog, a gulp of liquid

Smidiriní, fragments

Slisne, thin wede of wood

Spailpín, migratory labourer

Spairt, poor quality turf

Sponnc, energy

Stail, stallion

Stracail, struggling

Staimpi, potato cake

Straille, untidy girl

Sugán, rope of straw of hay

Suiste, flail for threshing

Taith-fheithleann, honeysuckle

Taoibhin, patch on the side of a shoe

Taoscán, a small quantity

Teaspach, exhuberance

Tathaire, impertinent boy

Tobar na carriage, well cut into a large rock on way to school.

Tochas, itch

Traithnín, strong blade of grass

Trom Lui, nightmare

Tri cois ceimeanna na trocaire, about turn and take three steps with oncoming funeral

Tuistiun, a four penny piece

Taoscan, a small quantity of liquid

Tri co is ceimeanna na trocaire, about turn and take three steps with oncoming funeral

Tóin, bottom

Tomhaisin, a small quantity

Tri-na-cheile, confused

Tuairgin, a pounder

Uisce beatha, whiskey

Uisce faoi talamh, intrigue

Utamail, fumbling, groping

These phrases were collected from the ordinary speech of Durrus people in the 1930s by Joe O’Driscoll NT, Dunbeacon.

Additional words

Buachallán, ragworth

Muise muise, exclamation wisha wisha mhuishe

Durrus/Cork c 1965

Scoraí (Scorai): Hawthorn Haw

A book published recently (June 2013) by Críona Ní Gháirbhith on the Irish of Co. Clare contains around 2,500 words and phrases. The publisher is COISCÉIM www.coisceim.ie

Phrases 19th century in old Irish with English translation. These were photographed by permission of Mr. Deacon, Skibbereen, Co. Cork, 1965. They may go back to mid 19th century for Skibbereen/Bantry area. he was born Co. Kerry 1895, living in Skibbereen 1911 with family father born Co. Wexford mother nee O’Herlihy and uncle James O’Herlihy, Pubican

https://plus.google.com/photos/100968344231272482288/albums/5960730933490243777

07 Friday Oct 2011

Posted in Uncategorized

The site irishgenealogy.ie has now put the parish records of the Muintervara parish online from 1820. In the absence of census records pre 1901 it is a valuable source of family information, for example the bulk of the birth records as well as itemizing the child, date of baptism, include the name of the mother and father and the sponsors. The town land is also given but to our modern eyes often in a rather corrupt version reflecting that many of the people in the early 19th century were Irish speaking and the priests were perhaps unfamiliar with local usages. The Church of Ireland records are not included perhaps in time they will be included. The existing Church of Ireland records are accessible in the library of the Rppresentative Church Body in Dublin.

A preliminary view of the records suggests a birthrate for the parish in the 1820s of c200 per year. What is also interesting is the interconnections between the minor landlord families in the period 1820-50 the O’Donovans of O’Donovan Cove/Fort Lodge, the Blairs of Blair’s Cove and the Evansons of various addresses in marriage patterns and was sponsors for each other.

07 Friday Oct 2011

Posted in Townlands

• Ahagouna (Irish: Ath Gamhna, meaning ‘Ford of the calves’). In Clashadoo town land.

• Ardogeena (152 acres) (Irish: Ard na Gaoine, meaning ‘Height of the flint stones’). On the east side is Lisdromaloghera (Irish: Lios Drom Luachra, meaning ‘Fort of the rushy ridge’)

• Ballycomane (1349 acres) (Irish: Baile an Chumain, meaning ‘town of the little valley’). Part of it is Ballinwillin with a boulder burial,with the remains of a millrace which may have been used by monks at the nearby church of Mouliward, ringfort and standing stone pair. Mass rock in Vincent Hurley’s farm. Former graveyard in Sam Attridge’s lands no remains. The oldest family are probably the Hurleys (Vincents), they moved from Ballnacarriga outside Dunmanway and Darby Hurley who held Ballycomane Middle was evicted by Lord Carbery when a rent payment was missed, the farm was then given to the Vickerys c 1770 Mountain ‘Sligeroct’ Little island on Four Mile Water 3 miles east of Durrus known as Gairdin na Mullagh after a priest’s curse.

Ballycomane is mentioned in a fiant of 1577 and a deed of 1594 where Walter Coppinger of Cork acquired various lands including a half ploughland formerly owned by Donghe McComucke McCarthy of Cloghane attained of high treason.

• Boolteenagh (148 acres) (Irish: Buailtinach, meaning ‘summer pasture’). The high land at the south is called Knockboolteenagh (cnoc buailtineach) hill of the little boolies. Site of a possible souterrain, at the north side is a ringfort.

• Brahalish (784 acres) (Irish: Breach Lios, meaning ‘spotted fort’) or Braichlis (place of malt or fermented grain). Mentioned in a fiant of 1577. On the west side is Brahalish Fort and the east Cummer Fort. In 1659 census written Bracklisse. Burial ground for children, horizontal mill stone with a rindbar near the farmhouse of David Shannon on the eastern side, ringforts. There is an oral tradition that there may have been a monastery at the area of this burial ground. Location of Brahalish gold fibula (clasp) currently in the British Museum. There are a series of walkways dating from at least the 19thcentury from the shore to the upper lands where people used to take baskets of seaweed to fertilize their small holdings.

• Carrigboy (116 acres) (Irish: Carraig Buidhe, meaning ‘yellow rock’). Location of Durrus village. The high road from here is built over land known as Carrig Cannon. Near the former farmyard of Denis Jl O’Sullivan now housing the remains of a souterain partly demolished during house building between the upper and lower road to Bantry.

• Curraghavaddra (195 acres) (Irish: Currach an Mhadra, meaning ‘the bog of the dog’). On the west side is a ringfort.

• Clonee (409 acres) (Irish: Cluain Fhia, meaning ‘meadow of the deer’ or ‘Aodh’s meadow’). In the cente is Clonee ringfort. Off the road near Jimmy Swantons is a disused quarry used in providing stone for tarring the Durrus/Bantry Road last worked in the hot summer of 1940.

• Clashadoo (749 acres) (Irish: Claise Dubha, meaning ‘dark hollows’). Burial ground last burial 1930s. To the north on high boggy ground is Coolnaheorna or Coornaheorna (this appears in the 1740 deed to Francis Bernard as a half ploughland) covering the former farms of Kellys and Sullivans leading to the ‘Cumar’, and beyond to Loch na Fola (lake of the blood). This may have been far more extensive in former times as the stream feeding it may have been diverted; the stream (Moire or in Irish Maighre) on the western end has a deep hole formerly known as Poul Nora Poll Nora (Nora’s hole). Between Rossmore and Mannion’s Island at half tide a rock ‘Carrig Coolnaheorna’ is visible; this marked the spot where people from Upper Clashadoo were entitled to take seaweed to fertilize their smallholdings. On the road to Coomkeen, at the eastern end is a graveyard used for unbaptised infants probably the site of Dun Clashadoo marked on the Ordnance Survey map. The ordnance survey map of 1842 shows ‘Cappanamanna’ on high ground to the west of the old rectory, it appears as ‘ a half ploughland at Cappamonagh’ in the 1740 deed to Francis Bernard and perhaps it may have some old connection with monks.

• Coolcoulaghta (1148 acres) (Irish: Cul Cabhlachta, meaning ‘remote place of the ruins’ or ‘cul cuallachta’ Nook of the tribe or assemblage. In the upper part is an area formerly called Cumha na acrai and the hill on top is Peakeen or Mount Corrin. Location of boulder burial, burial ground at cilleen for unbaptised infants. Coolcoulaghta Church contains 1847 famine victims, cairn, coastal promontory fort, fulachta fiadh, ringfort, standing stone, a standing stone pair. Sub townland Gaulan after two ogham staones.

• Coomkeen (915 acres) (Irish: Cum Caoin, meaning ‘gentle valley’). Mass rock on the lands of Timmy Whelehan deceased known as Tober an tSagairt, on the south side is Screathan na Muice (stoney slope of the pig) this is given as the address of one of the Dukelows in the 19thcentury, c 1850, marriage register of St.James’s church., to the north is Crock a wadra. On the flat bog before the turn for Clashadoo are clay pits on the right used for road making. The Coomkeen farmers had rights to sea wool between what is now the pier and the sand quay used to fertilize their holdings.

• Crottees (490 acres) (Irish: Cruiteanna, meaning ‘humpy ridges’), location of large stone associated with Dukelow family

• Dromreagh (842 acres) (Irish: Drom Riabhach, meaning ‘striped/grey ridge’). Mentioned in the Calendar Patent Rolls of 1620. On the north side is Coill Breach (wolf wood). Possible souterrain, standing stone.

• Dromatiniheen (97 acres) (Irish: Drom a’tSionnaichin, meaning ‘ridge of the little fox’). Ringfort on the south side.

• Dromreague (92 acres) (Irish: Drom Reidh, meaning ‘even ridge’)

• Dunmanus (Irish: Dun Manus, meaning ‘fort of Manus’)

• Durrus (Irish: Dubh Ros, meaning ‘dark wooded promontory’)

• Gearhameen (646 acres) (Irish: Gaortha min, meaning ‘small wooded glen’). On the east side is Coolnalong Castle seat of the McCarthy Muclaghs later the property of Lord Bandon. On the Clashadoo side is Fahies (na Faithi) containing a disused quarry operated by the Spillane family used to provide stone for the Catholic church.

• Gurteen (127 acres) (Irish: Goirtin, meaning ‘small field’)

• Kealties (614 acres) (Irish: Caolta, meaning ‘narrow strip of land/or marshes marshy streams’). Mentioned in the Calendar Patent Rolls of 1616. On the south side is Ros na Bruighne (headland of strife), written Glinkelty (Gleann Caolta) on 17th century map of Petty. Standing stone and possible ringforts. The high ground was known as Caolagh.

• Kiloveenoge (Irish: Cill Ui Mhionoig, meaning ‘Minogue’s church’, or Cill Oighe Mhineogmeaning ‘church of the virgin Mineog’). Mentioned in the Calendar Patent Rolls of 1616. Child burial ground, on the east side is a former Protestant Church built 1860, the west side is the site of an old church and burial grounds. Some distance from where Mike Hegarty’s sop was located is a grave of sailors who were shipwrecked, marked with thorn bushes, possibly from c 1850.

• Lissareemig (78 acres) (Irish: Lios a’Riamaigh, meaning ‘fort of victory’). Ringfort in centre.

• Mannions Island, used c 1900 by the Philips family for horses.

• Moulivarde (Irish: Meall an Bhaird, meaning ‘the bard’s knoll’), site of old Durrus Church and graveyard.

• Mullagh (173 acres) (Irish: Mullagh, meaning ‘summit’). Possible souterrain on the west side is Lissavully Fort (lios a’Mhullaigh) fort of the summit.

• Murreagh (199 acres) (Irish: Muirioch, meaning ‘seaside marsh’). Location of disused grain store also used as a refuge for children in 1847. Disused slate quarry south end also standing stone.

• Parkana (Irish: Pairceanna, meaning ‘fields’)

• Rooska West (298 acres) East (295 acres) (Irish: Riasca, meaning ‘marshes’). Mentioned in the Calendar Patent Rolls of 1612. Disused lead mines on western side ringforts in West and East. On Ordnance Survey Name Books reference to a burial place for small pox victims then (1840s) disused.

• Rossmore (310 acres) (Irish: Ros Mor, meaning ‘large copse or large promontory’). Location of Rossmore Castle in ruins former O’Mahony tower house and location of former slate quarry. In the field west of Attridges off the road there is believed to be a famine graveyard as told to Nancy Dukelow by her father Tom. This may be in fact the graveyard marked ‘cillin’ on the ordnance survey map to the east of Attridges in Jimmy Hegarty’s yard which David Shannon of Rossmore says may also have been the site of an old church or a pre workhouse refuge for destitute people.

• Rusheenasiska (84 acres) (Irish: Ruisin an Uisce, meaning ‘little copse of the water’)

• Teadagh ( 107 acres) (Irish: Taodach, meaning ‘rugged land’ or Teideach, meaning ‘flat topped hill’)

• Tullig (Irish: Tullach, meaning ‘mound’), location of O’Donovan houses at the Cove and Fort Lodge.