The case for Rural electrification

Work did not start on rural electrification until the end of the Second World War or as it was called in Ireland the ‘Emergency’.

It was not until the Rural Electrification Scheme (1946) and the Electricity Supply Amendment Act (1955) were passed that the electricity network started to reach the most rural and isolated communities in the country.

Dr Thomas McLaughlin, the driving force behind the Shannon project and now the Managing Director of the ESB believed that rural electrification represented:

‘the application of modern science and engineering to raise the standard of rural living and to get to the root of the social evil of the “flight from the land”.‘ (5)

It was hoped that electrification would ‘raise the standard of rural living and get to the root of the social evil of the “flight from the land”.‘

The task that faced the ESB was herculean, a suitable modern-day comparison would be the challenge the state has in installing rural broadband. Thankfully in the ESB the state had an organisation with men and women up to the task.

The State was divided into 792 areas – roughly along parish boundaries. This was a clever strategy as the ESB recruited at least one local influencer in each area who could encourage their friends and neighbours to sign up to get connected to the new network.

Rural electrification began in earnest when the first pole in phase one was raised on November 5th, 1946, at Kilsallaghan, in north Co Dublin. The first lights of the scheme were switched on at Oldtown, Co Dublin, in January 1947. (6)

Promoting Electricity to Rural Ireland

One of the most potent propaganda tools in rural Ireland at the time was the parish priest in the pulpit. Throughout rural Ireland the ESB worked with the local clergy, who were then used to extoll the virtues of the new technology and the benefits of electrification.

Although it would never be economically viable to connect some sparsely populated areas the strategy was simple, the more people who wanted a connection the sooner their area would be visited and worked upon.

The approach in every district was the same. The ESB asked householders if they wanted to sign up for electricity, then held local information meetings.

In the first long phase of electrification, which ran from 1946 to 1965, it was sometimes your hard luck if you wanted to be connected but your nearest neighbours did not.

From the 1940s to the 1960s, householders signed up voluntarily to be connected to electricity. Not all wanted, or could afford to.

This was because the ESB deemed it uneconomic to run lines to just one house. The areas with the highest take-up were first to be connected.

Although some people did not want change, and others worried about whether the wires might set their thatch roofs on fire, most people who refused connection did so for financial reasons.

That “uneconomic acceptance” was a category on the forms which showed how widespread rural poverty was. The scheme was heavily subsidised, but, depending on the size of the premises, householders had to pay a connection fee, along with future bills, and to wire their homes before they were connected.

The people who first agreed to sign up but then changed their minds were called ‘backsliders’.

In May 1954, in Ballivor, Co Meath, 290 people said they wanted electricity. Nineteen changed their minds, for reasons that are stark examples of poverty in 1950s rural Ireland such as:

“No funds. House semi-derelict.” “Refused supply due to lack of funds.” “Has large family and could not pay fixed charge.” “Both labourers out of work.” “Recently widowed. No funds.” (7)

Throughout the length and breadth of Ireland politicians of all political shades lobbied the ESB for their area to be electrified. It wasn’t just politicians who tried to exert their influence

In July 1957, the parish priest of Ballycroy county Mayo wrote to the Rural Electrification Office. He said that his parishioners were anxious and that they believed he could influence decisions at the Dublin head office. “Sometimes people get an idea that the PP isn’t taking any interest in these matters. I need not add that I have a very deep interest in the light coming to Ballycroy.” (8)

Sadly, his appeal fell on deaf ears, due to economics and it wasn’t until April 1964 before electricity at last came to the parish.

A Herculean effort

The Rural Electric Scheme was a massive project, the work would require over 1 million poles erected with 78,754km of wire used. It would eventually cost £36m equivalent to €1.5bn today.

The first phase of the scheme ended in 1965 and by then, over 300,000 homes were connected.

Post-development plans and extensions ran until 1978 when Blackvalley, Co Kerry received electricity. By 1975, 99% of Irish homes were connected to the same electricity grid.

The Rural Electrification Scheme employed up to 40 separate units of 50-100 workers, spread across 26,000 square miles. Many of these units were stationed in remote localities, and daily face-to-face communication was impossible. (9)

By 1975, 99% of Irish homes were connected to the same electricity grid.

Such a widely dispersed workforce presented the Rural Electrification Office (REO) with a challenge – how could it ensure fast and efficient communication among its staff?

The solution was suggested by the chief engineer in charge of the project William Roe who quickly recognised the vital importance of good communication across the nation to ensure the success of the scheme. He told the ESB:

“If a high standard of performance was to be achieved, the staff needed not alone to be well briefed and motivated from the start, but to be constantly refreshed with information on the progress of the scheme, advised of developments in all aspects of the work, sustained when difficulties arose and motivated to give of their best at all times” (10)

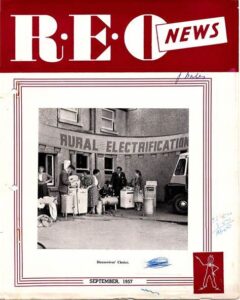

Roes’ solution was simple but innovative for the time he created a magazine for employees called REO news.

In December 1947, the first edition informed all those working on the scheme that:

“In order to keep the rural staff informed of the progress of the rural Electrification scheme it is intended to issue REO news monthly”. (11)

It covered a variety of topics, including personnel and transfers of staff; the delivery and distribution of materials; sales figures and league tables; area notes; engineer and progress reports; news items and articles of interest; as well as sports and social pages, letters to the editor, and photographs.

A focus on progress, staff league tables and sales figures all succeeded in instilling a sense of rivalry among the workers, inspiring them towards greater effort.

There were 168 issues of REO News published between December 1947 and November 1961, growing from 3 to over 20 pages. In 1953, the magazine was given a glossy cover, and included a number of black and white photographs, and by 1959, REO News was published in a fully printed format. From 1948, REO News also printed a special December issue. (11)